- Elena Hartmut

- Jul 21, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Jul 30, 2025

COVER TO COVER

HILDEGARD VON BINGEN: THE ORIGINAL POLYMATH

ELENA HARTMUT

July 21, 2025

Hildegard von Bingen lived a thousand years ago, yet her thought—spanning cosmology, music, medicine, and mysticism—feels uncannily contemporary. In an age that segregated knowledge according to gender, discipline, and doctrine, she refused every category. This essay traces Hildegard as the first true polymath, one who wrote from the edge of the known, where insight meets embodiment and thought begins to sing.

Some thinkers labor within the knowledge they inherit. They refine its categories, buttress its foundations, and work with measured discipline inside its given walls. And then there are those who think from the threshold—one foot planted in the sanctioned world, the other reaching into what cannot yet be named. These minds do not merely combine disciplines or cross domains; they inhabit the friction between them. Their thought is not additive, but transformative.

Hildegard von Bingen was such a thinker. And in many ways, she was the first.

Shelves, both real and digital, are already heavy with books, translations, and archives on Hildegard von Bingen, yet what follows is not another dutiful exegesis. Think of it instead as a brief, immodest reminder of just how radically visionary she was, and how urgently her way of thinking resonates in our fractured, distracted times.

Born in 1098 in Bermersheim vor der Höhe, a small village in the Rhineland near Mainz, Hildegard (who died in 1179, aged eighty-one) entered a world shaped by crusades, famine, celestial fear, and ecclesiastical absolutism. Knowledge was controlled by the Church, bound in Latin, and kept behind monastery walls. The intellectual life of the twelfth century was not simply male-dominated—it was male-defined. Women were forbidden from preaching, excluded from universities, and barred from theological speculation. Books were rare, copied by hand. Literacy itself was suspect if possessed by the wrong body. To be female and intellectually ambitious was to be both invisible and transgressive.

And yet, against all odds—and perhaps because of her enclosure—Hildegard emerged.

“The Fall of Sins,” illumination III from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

Following Hildegard’s depiction of the divine kingdom in the opening vision, this illumination presents the pages of Holy Scripture as striking, almost otherworldly images. The vision, known as The Fall of Sins, unfolds around three intertwined themes: the origin of evil, the relationship between man and woman, and the promise of redemption and salvation.

She was given to the Church at the age of eight, entrusted to a small stone cell at the monastery of Disibodenberg. She joined Jutta von Sponheim, an anchorite, and for decades remained cloistered, observing the rigid rhythms of monastic life: fasting, silence, psalmody. It was an architecture of withdrawal. But from within that architecture, her mind bloomed—dense, radiant, unruly. She later wrote that her visions had been with her since childhood, but she had hidden them for fear of persecution. Only in middle age, after years of illness and dread, did she finally consent to write.

She was a visionary composer, mystic, and natural philosopher in an age that permitted women none of these vocations. Before interdisciplinarity had a name, Hildegard embodied it—rooted in the cloister, reaching into the cosmos.

Her first great work, Scivias (Know the Ways, completed ca. 1151), is neither treatise nor tract but something far stranger and more luminous: a series of thirty-five visionary illuminations (nine of which accompany this essay), based on twenty-six of her most vivid visions and dictated to her under what she called “the living light”—a radiance she experienced not as metaphor but as force. The visions are structured, architectural, diagrammatic. They map the cosmos, the soul, the fall of angels, the birth of time. But they are also ecstatic, lyrical, disturbingly embodied. The language is formal but trembling, filled with fire-eyed beasts, cosmic wombs, celestial rivers. Hildegard did not merely describe the divine—she staged it.

Scivias was followed by two even more ambitious works: Liber Vitae Meritorum (Book of the Rewards of Life, ca. 1158–63) and Liber Divinorum Operum (Book of Divine Works, ca. 1163–73), in which Hildegard constructed a comprehensive cosmology that wove together metaphysics, morality, astronomy, music, and physiology. These were not devotional texts. They were systems of thought—early attempts to reconcile the material and the mystical, the terrestrial and the divine.

“The Soul and Your Pavilion,” illumination V from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

This vision traces the entire arc of human existence, beginning with the first stirrings of life within the mother’s womb and culminating in the final separation of spirit from the body. It is a meditation on both the fragility and the transcendence of the human condition, mapping the soul’s journey from its earliest, hidden origins to its ultimate release. The depth and richness of these ideas are distilled into three distinct miniatures, each functioning as a self-contained revelation—intimate vignettes that together form a greater narrative of creation, fall, and redemption.

And, remarkably, she was listened to. She wrote letters to abbots, bishops, emperors, and popes. She rebuked clerical abuses, interpreted omens, issued prophecies, and corresponded with power. Pope Eugene III read aloud from Scivias at the Synod of Trier. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa received her warnings. She chastised the Archbishop of Mainz. In a world where women were expected to serve in silence, Hildegard spoke as if history itself depended on her piping up. Her legitimacy rested on her constant insistence that she was a mere vessel, that the voice was not hers. But no vessel writes like this, composes like this, organizes monasteries, debates bishops, authors medical encyclopedias, and still has breath left to sing.

Hildegard was not content to be one kind of thinker. Her mind was polyphonic. She composed more than seventy liturgical chants—music that stretched the bounds of medieval plainchant. Her melodies are long, fluid, almost vertiginous. Lines ascend and hover, as if reaching for the source of breath itself. Unlike the tight austerity of Gregorian chant, the compositions move with a freewheeling verticality, as though unconcerned with gravity. They are unanchored, ecstatic, and often demand vocal ranges far beyond the norms of the time.

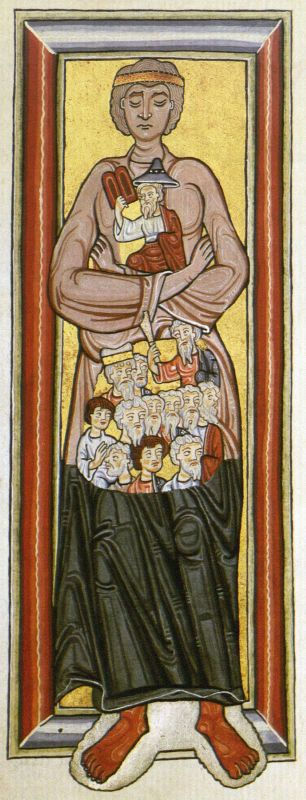

“The Synagogue,” illumination V from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

In this miniature, we encounter the face of a sorrowful woman, a personification of the synagogue in the medieval imagination. Yet unlike the conventional depictions of the synagogue as a blindfolded figure bearing a broken scepter—a symbol of defeat and spiritual blindness—Hildegard’s Scivias presents a woman of striking beauty, imbued with dignity and self-possession. Through this image, Hildegard dares to affirm the enduring worth of the Jewish faith, even in an era scarred by persecution and division.

Hildegard’s most ambitious musical work, Ordo Virtutum (The Play of the Virtues, ca. 1151), defies easy classification. It is part morality play, part liturgical drama, part metaphysical opera. The characters are personified virtues—Knowledge, Humility, Obedience—and they are all female. They sing in voices of unison and variation, coaxing a fallen soul back into alignment. The Devil, the sole male character, is the only figure who does not sing. He speaks, gutturally and rhythmically, but cannot join the celestial harmony. For Hildegard, music was not an embellishment—it was ontology. To sing was to be attuned to creation itself. The Devil’s exclusion from music is not dramaturgical, but metaphysical. He is literally out of tune with the cosmos.

Hildegard believed that before the Fall, human voices had been in perfect consonance with the harmony of the spheres. Her music was an attempt not to imitate beautym but to restore it—to re-attune fallen beings to their original, forgotten frequency.

“The Visionary,” illumination I from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

This miniature portrays Hildegard receiving and recording her visions, surrounded by divine flames, while her assistant, Volmar, documents the revelations. Positioned at the preface of the text, this illumination symbolizes Hildegard’s calling from God to serve as a prophet. The scene corresponds to her account in the Scivias preface of the visions she experienced in 1141, at the age of forty-three.

And so, her music is not supplemental to her thought. It is her thought. Her chants, her diagrams, her visions, her medical writings—these all emerge from the same cosmology, one in which the intellect and the senses are inseparable, where the body is a vessel of insight and the cosmos is made legible not only through reason, but through song.

“Motherhood from Spirit and Water,” illumination XIIV from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

This illumination explores the unfolding of salvation within the Church and through its sacraments. In this particular miniature, the essence of the Church is symbolically portrayed, while the sacrament of baptism is evoked through partial, emblematic representations rather than a single literal scene. The imagery suggests both the mystical body of the Church and the transformative power of baptism as an entry point into divine grace.

At the same time, Hildegard wrote treatises on medicine, the properties of plants and stones, the causes and cures of illness. Her Physica (ca. 1150–60) is a natural history of flora and fauna. Causae et Curae (Causes and Treatments, ca. 1161) is a medical compendium of diagnoses, treatments, and theories of disease, filtered through a humoral and astrological lens. But even here, Hildegard did not divide knowledge into compartments. The human body was a mirror of the macrocosm. The blood was lunar. The organs were moral. Disease was not merely a physical rupture, but a symptom of metaphysical dissonance.

What she offers, still, is a model of thought that refuses division. Her concept of viriditas—greenness, vitality, the generative force that pulses through all living things—appears in her theology and her healing alike. It links the vegetal and the divine, the planetary and the fleshly. Her cosmology is a living ecosystem. It breathes.

“The Sacrifice of Christ and the Church,” illumination XV from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

This vision reveals the mystical origin of the Church, weaving together themes central to the celebration of the Holy Mass and the sacrament of the Eucharist—motifs that run prominently through the middle sections of Scivias, particularly its second part. In this miniature, the Church is personified as the bride of Christ, standing beneath the cross. She receives the flesh and blood of Christ as the dowry of her divine bridegroom, a sacred gift that she offers anew during the Holy Mass before God. The image becomes both a theological statement and a visual hymn to the intimate bond between Christ and his Church.

To think like Hildegard is to refuse to separate insight from embodiment, doctrine from intuition. But the threshold is not a safe place. It is unstable, often punishing. Hildegard collapsed repeatedly under the pressure of her revelations, falling ill when she refused to speak what the voice demanded she write. Her obedience to the vision was not a gesture of piety, but a form of survival. The edges of disciplines, like any sacred space, exacted a toll.

That she did all this nearly a thousand years ago is not just astonishing—it is almost inconceivable. She predated René Descartes by half a millennium, Galileo Galilei by four centuries, and Leonardo da Vinci by more than three. What we later came to call the “Renaissance man”—the figure who moved between disciplines, who fused the aesthetic and the empirical—was already realized in Hildegard long before the Renaissance had a name. She was a polymath in an age that had no language for one. Unlike her later male counterparts, she operated without institutional permission, without patronage, and often without protection. She stood not just outside her own time, but in many ways above it: sui generis, unsponsored, unduplicated.

If Hildegard dreamed in light, what do we dream in? The contemporary world celebrates interdisciplinarity, parades hybrid titles, and funds initiatives in “transdisciplinary innovation.” Writer-curator. Designer-researcher. Artist-educator. University brochures trumpet “cross-sector fluency” and “collaborative futures.” But often this is branding disguised as thought. What passes for fusion is too often mere adjacency. The scientist and the artist share a table but not a method. The theologian and the coder coauthor a paper no one reads. Thresholds are endlessly invoked, yet almost never entered.

“The Enemy Bound,” illumination XVII from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

This image marks the concluding vision of the second part of Scivias and is rendered across two miniatures. It centers on the destructive work of the Devil and the vices that emanate from his influence, portraying the relentless struggles faced by believers when confronted with evil. Through its stark contrasts and symbolic forms, the vision becomes a meditation on spiritual warfare—an unflinching depiction of humanity’s battle against temptation, corruption, and the forces that seek to pull the soul away from divine grace.

To think from that precipice is rare because it courts disorientation. It does not merely borrow from other fields; it exposes the foundations upon which those fields stand. It questions the taxonomy of knowledge itself. Institutions crave novelty, but within familiar metrics. Hildegard offered neither. She was too mystical for science, too empirical for religion, too poetic for doctrine. But perhaps that unreadability is the point. Her legacy is not clarity—it is resonance. She reminds us that thinking is not always about resolving. Sometimes it is about vibrating in tune with what exceeds our comprehension.

Hildegard did not perform integration. She embodied it. Her voice was not a convergence of disciplines but a refusal of division altogether. Her theology was musical. Her music was medicinal. Her medicine was planetary. Her cosmos was alive.

“The Great Day of Revelation,” illumination XXXIII from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

In this illumination, God unveils to Hildegard the vision of the world’s end, when the Son of God returns to deliver the final judgment. The collapse of the cosmos is mirrored in the death of humankind, as the fate of the individual and the destiny of the world are bound together in a single, ultimate reckoning.

Hildegard remains urgent not because she anticipated our world, but because she transcended her own. She speaks to those who live between languages, between roles, between epistemologies. To write from the threshold is to risk everything—coherence, legitimacy, recognition. But it is also to stand, as Hildegard did, in the living light. Not as authority, but as witness.

Elena Hartmut (b. 1969 in Liechtenstein) studied medieval theology in Aarhus, Denmark, and at the Warburg Institute in London, and has been writing about ecstatic knowledge and visionary nuns with suspicious confidence ever since. She teaches grudgingly in Edinburgh and lives alone in a stone cottage somewhere north of Inverness.

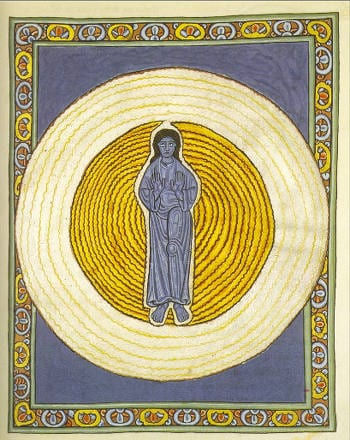

Cover image: “True Trinity in Unity,” illumination XIII from the Rupertsberg Scivias-Codex

This miniature is among the most celebrated images from the original Scivias codex. It visualizes the unity of the Divine Trinity through a strikingly simple yet profound composition: a sapphire-blue human figure encircled by concentric bands of shimmering gold, set against a vast, radiant background framed by an ornate border. Streams of light emanate from the background, heightening the interplay of color and form and drawing the viewer’s gaze toward the luminous center. The effect is both austere and transcendent, a visual theology rendered through elemental shapes and radiant hues.

Wild, thank you!