- C. Everett Faulkner

- Mar 13, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 26, 2025

COVER TO COVER

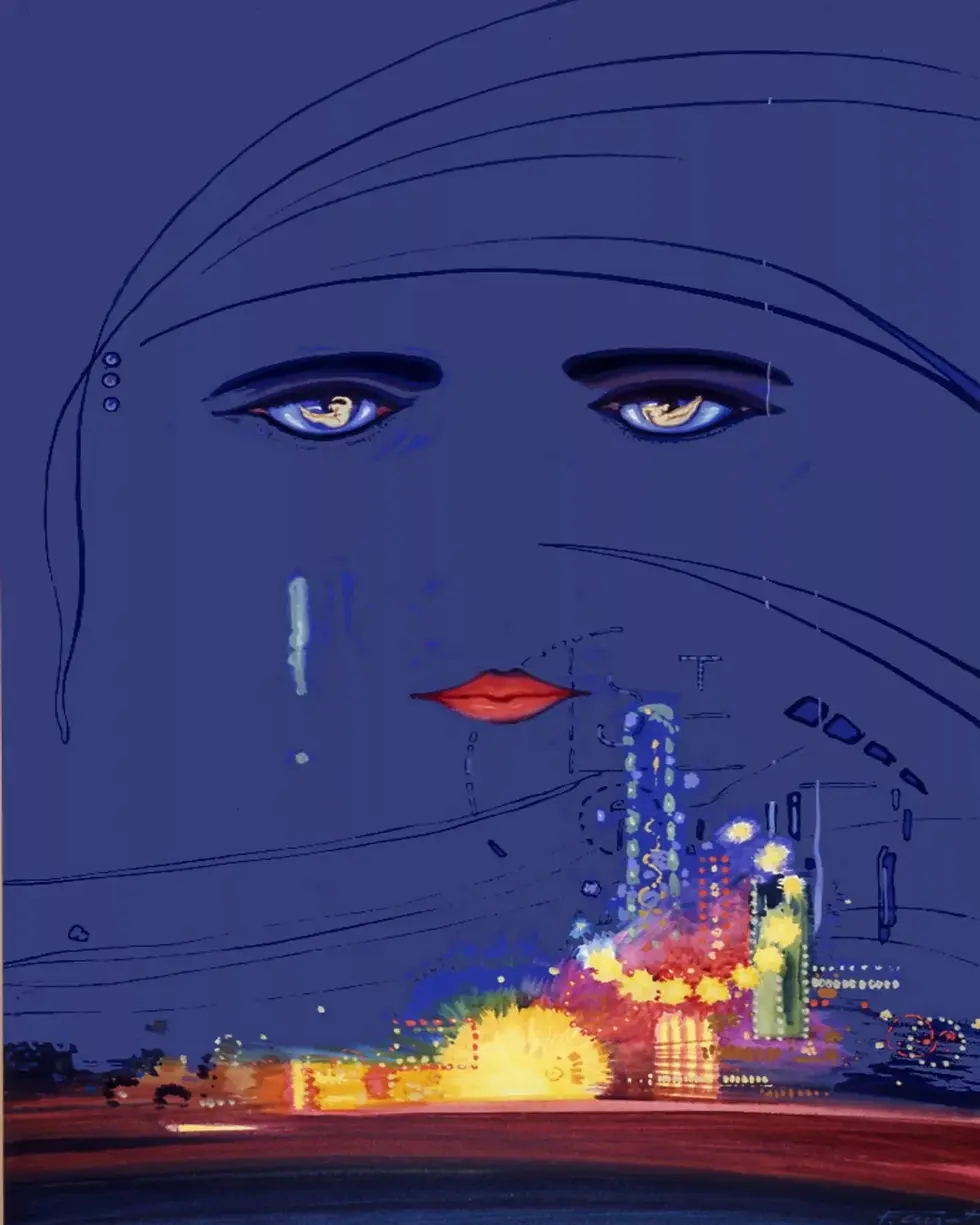

OF GREAT RELEVANCE: WE ARE ALL GATSBY

C. EVERETT FAULKNER

March 13, 2025

First published a century ago, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” (1925) explores enduring themes of wealth, ambition, and the American Dream—ideas that continue to shape society. In an era of extreme inequality, social media spectacle, and the relentless pursuit of status, Gatsby’s longing for an idealized past reflects modern anxieties about success and reinvention. The novel also critiques the emptiness of materialism and the illusion of meritocracy, making it especially relevant in discussing privilege and economic disparity. Its themes of love, loss, and identity remain deeply resonant, securing its place as a lasting cultural touchstone.

Few novels have captured the American imagination as profoundly as The Great Gatsby. Published in 1925, the novel remains an ever-haunting specter of ambition, longing, and the grotesque theater of wealth. It continues to fascinate, not merely as a relic of a bygone era but as a prophecy of the unrelenting, illusory pursuits that still shape American culture. But what is it exactly that makes F. Scott Fitzgerald, that melancholy conjurer of lost dreams, whisper across the ages? If the novel lives, it is because we still have not awakened from its trip.

Summer 1922. Nick Carraway, reluctant witness to an unraveling mythology, moves to West Egg, Long Island, and finds himself orbiting the shimmering vision that is Jay Gatsby. The man of the hour, the man of the decade—a host, a shadow, a hopeful ghost—lives in desperate hopes of reclaiming Daisy Buchanan, his one longing, his fixed point in an ever-expanding void. But love, as Gatsby dreams it, is an illusion built on sand. Time resists manipulation, the past refuses to be rewritten, and so the dreamer must fall. As Gatsby reaches for Daisy, he goes for a world that does not, and never did, exist. And so, with poetic cruelty, he meets his end. In a case of mistaken vengeance, a bullet cuts short his splendid fantasy, leaving behind only the slow, drowning echo of a dream collapsing.

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald

But what if Gatsby’s pursuit of Daisy is only a symptom? What if his desire is more sinister, something akin to necromancy, an attempt to wrench back time itself? The Great Gatsby is often read as an elegy to the American dream, but it reads just as well as a ghost story, a tale of spectral ambition and feverish reinvention. Gatsby is no mere bootlegger; he is a phantom architect of his own kingdom, living in a self-spun fable where the past can be bargained with and memory remade. Today’s world is filled with its own Gatsbys, shaping identities in the flickering glow of digital screens, each post and curated snapshot another desperate offering to the gods of perception. Social media is the new East Egg, its denizens wading through an endless masquerade of champagne-tinted nostalgia, forever hoping to manipulate how they are seen, never quite knowing if the illusion is theirs or another’s entirely.

If Gatsby is a man trapped in the past, The Great Gatsby is a warning disguised as a love letter. The green light, often interpreted as hope, is a cruel taunt. Gatsby’s parties, framed as grandiose indulgences, are carnivals of quiet despair, where strangers gorge themselves on luxury, then leave behind empty bottles and unspoken regrets. Fitzgerald does not romanticize excess; he curates it, embalms it, lays it out like a decadent corpse for us to examine. He foresaw, perhaps, the neon glow of our contemporary decadence, our obsessive hunger for spectacle that devours meaning. Gatsby is alive in every red-carpet event, in every billionaire seeking immortality, in every algorithm designed to feed us a dream.

Grand entrance

Even Fitzgerald’s influence is shadowed by irony. His elegant prose and cutting metaphors have shaped generations of writers, but one wonders if they have understood the darkness in his words. The unreliable narrator, polished to perfection in The Great Gatsby, echoes in the delusions of Fight Club (book 1996, film 1999), in the cold detachment of American Psycho (book 1991, film 2000). The green light has become more than a motif; it is a cultural artifact, a cipher for all that remains just beyond reach. Jay-Z’s contribution to the 2013 film adaptation was more than a soundtrack—it was a knowing wink, an admission that Gatsby’s hunger for reinvention still courses through American veins.

Daisy Buchanan

And what of Fitzgerald himself? The man, like his creation, lived his myth too fully. He danced on the edge of excess, wrote of its poisons even as he sipped them. His early triumphs faded too soon, and by the time of his early death in 1940, The Great Gatsby had been reduced to the back rooms of bookstores, ignored and forgotten. Like Gatsby, Fitzgerald died with a dream unrealized, and only in death was he resurrected, his novel rising from obscurity to claim its place as one of the defining works of American literature. He, too, became a ghost—this time, one who lingers in the minds of every reader who has ever been seduced by a beautiful dream.

Perhaps this is why The Great Gatsby persists. It is a novel of dualities: beauty and rot, grandeur and ruin, longing and loss. We analyze its themes, but in the end, we are simply enthralled. There is something in its atmosphere, its hypnotic rhythm, its slow and inexorable unraveling, that grips us even as we recognize the inevitability of its tragedy. The hollowness at its core is not just Gatsby’s, not just Fitzgerald’s, but ours. We carry the novel with us because we recognize something of ourselves in it: the urge to reach for something just beyond the horizon, to rewrite our own fates, to chase a sensation until it consumes us.

Consider the peculiar details that make its legend all the more spectral. The novel’s original title, Trimalchio in West Egg, alluded to an ostentatious Roman figure, a parallel that suggests Fitzgerald always knew Gatsby was a man out of place, an emperor without an empire. The inspiration for the character may have come from Max Gerlach, a bootlegger Fitzgerald knew, who staged his life with the same flair for reinvention. Even Zelda Fitzgerald’s claim—that Daisy’s words were taken from her own letters—feels like another instance of Fitzgerald blending fiction and reality until they could not be cleanly separated. The novel’s initial failure almost seems preordained, part of its myth. It was meant to rise from its own ashes, as Gatsby rose from James Gatz, as every dreamer tries to rise beyond their own shadow.

More like a decade

And so, we return to the question: Why does The Great Gatsby refuse to die? Because it is not merely a novel, but a warning, a mirror, a ghost story whose spirits still whisper through time. Fitzgerald’s words are not frozen in 1925; they are with us now, every time we scroll through curated dreams, every time we chase something we can never quite hold. We are Gatsby, standing at the water’s edge, reaching toward the green light, forever believing we are almost there.

C. Everett Faulkner (b. 1980 in Bristol, UK) writes like a historian with a poet’s hangover, unearthing America’s old myths and polishing them to a sharp edge. His books and essays turn nostalgia into tales from the crypt. A literary critic with a taste for lost causes, he digs up the past to prove it never really died. He lives somewhere between the faded ink of old cocktail recipes and the glow of smartphone screens—though officially he resides in New Orleans, a city that suits his obsession with history, reinvention, and the ghosts of American ambition.

Cover image: cover art for the 1925 first edition based on the painting Celestial Eyes (1924) by Spanish artist Francis Cugat

Comments