- Marjorie Ames

- Nov 5, 2025

- 9 min read

COVER TO COVER

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO MARTHA

MARJORIE AMES

November 4, 2025

Before there were influencers, there was Martha Stewart. When her book “Entertaining” first appeared in 1982, it turned the domestic table into a moral stage and its author into an American oracle of order. The new reissue this week arrives like a ghost from a time when it was still possible to believe that perfection could be practiced—one canapé, one folded napkin, at a time.

It returns with the same dust jacket, the same portrait of its author leaning confidently over an immaculate dining table. The reissue of Entertaining by Martha Stewart, the original lifestyle industrialist, arrives this November not as a novelty but as a resurrection: a book exhumed from an age that believed in perfection as both lifestyle and moral code. When it first appeared in 1982, Stewart’s debut was neither a cookbook nor a design manual, but a liturgy—a vision of a nation still young enough to believe that civility could be baked, polished, and arranged into being.

The 2025 reissue of Entertaining—same dust jacket, same calm light, same promise of order

I saw the new edition the other day in a bookstore window. The same serif type, the same soft lighting, the same impossible calm. The world outside had changed—the traffic louder, the interiors rougher, the idea of “entertaining” reduced to a delivery app and a half-clean kitchen. Yet there it was, unaltered, as if untouched by the forty-three years between Reagan’s first term and whatever we are living through now. Even the publisher insists that nothing has been changed—not the language, not the photographs, not the tone of absolute authority. The past, it seems, has been reissued without revision.

Opening the book feels like entering a reliquary. The paper is heavy, creamy. The photographs are lit like Renaissance paintings of domestic divinity. A salmon mousse gleams beneath a dome of aspic. Glassware multiplies like a cathedral’s crystal organs. Women in silk dresses smile without irony, holding dishes that look more architectural than edible. There is an air of consecration. Entertaining is not about pleasure, or even taste. It is about the possibility of control—the faith that chaos can be conquered by presentation.

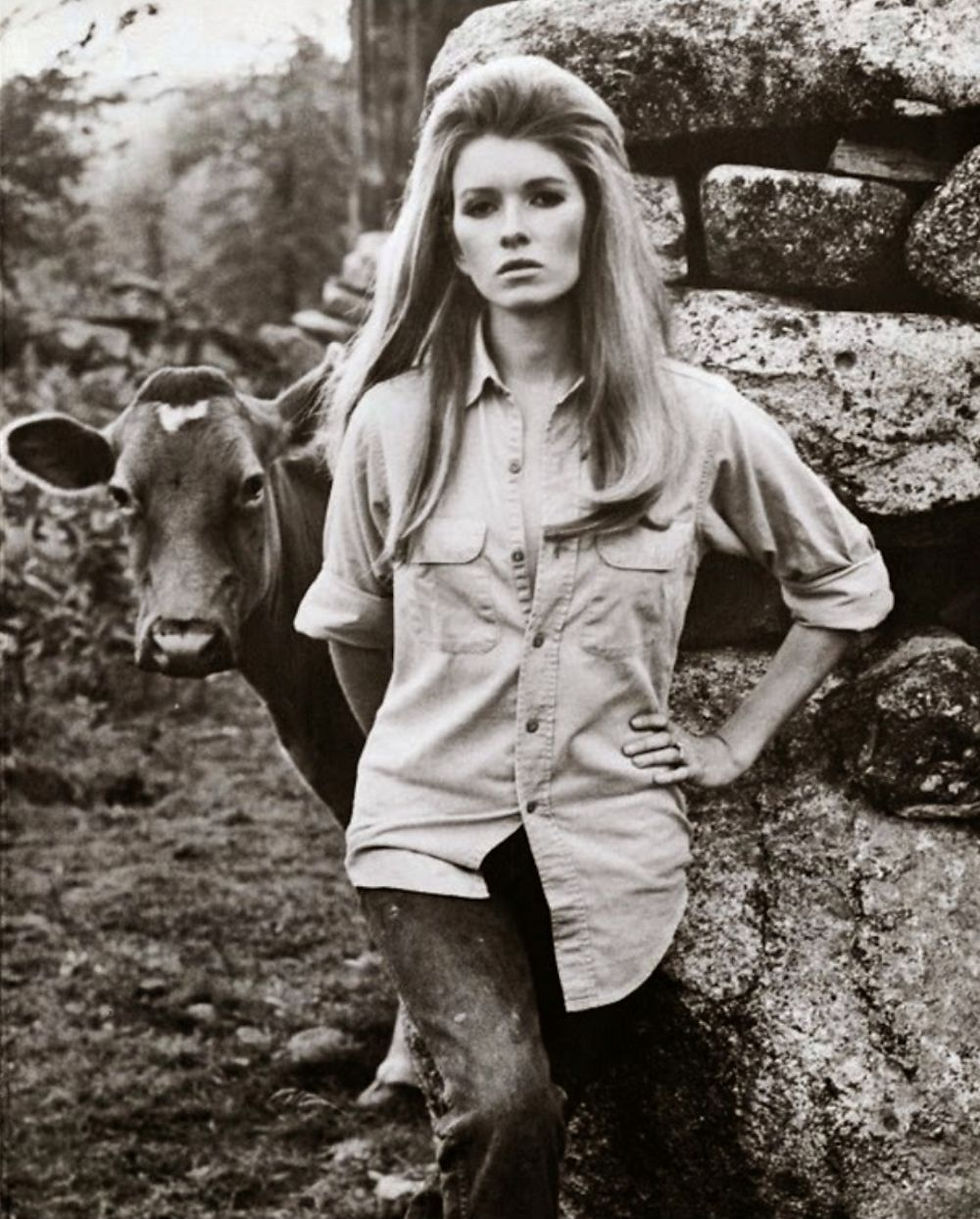

Before the empire: Martha Kostyra, the model who would later teach America how to fold napkins as if they were commandments

A former model turned caterer, Martha Stewart transformed the private rituals of domestic labor into a public theology. Entertaining was her Book of Genesis. She treated hospitality as a moral act, as though the republic itself might collapse if the soufflé fell. Beneath the pastel calm of her prose runs a deeper current—the conviction that home can be both sanctuary and stage, that the host is not merely serving food but shaping civilization.

This was 1982: the dawn of Reagan’s America, when aspiration replaced dissent, and the dream of self-improvement reached its glossy apotheosis. A new moral economy was taking shape, measured not in political conviction but in personal refinement. If the 1960s had been about freedom, and the 1970s about survival, the 1980s were about presentation—the right crystal, the right canapé, the right light at 7:45 p.m. Martha Stewart’s genius was to turn all that anxiety into confidence. She promised not just good taste but moral superiority, a form of redemption available at the kitchen counter.

To read Entertaining now is to encounter an America that believed in mastery. The book assumes a reader who has time, space, money, and a reliable florist. Yet what fascinates is not the privilege but the belief—the serene certainty that the right arrangement of objects will hold the world together. The American dream, distilled through Stewart’s lens, was not freedom but order. Even chaos had to be planned for: hurricanes of guests tamed into seating charts, the unpredictable nature of appetite pacified by appetizers arranged in concentric circles.

It is impossible not to admire the precision. Each page reads like choreography, with guidance so meticulous that even the placement of chairs and flowers becomes a moral proposition. Conversation must flow; sight lines must be balanced; the room itself must perform harmony. It is a small democracy of gestures, as if the table could model the nation itself: egalitarian, symmetrical, perfectly lit.

But admiration quickly gives way to unease. The perfection begins to shimmer into tyranny. Entertaining is a world without dust, accidents, or improvisation. It is a republic of surfaces, where labor disappears and pleasure is domesticated into performance. Stewart’s prose rarely laughs, and her guests rarely move. Every image is a still life of control—which, when you think about it, is the opposite of hospitality, which depends on unpredictability, on the arrival of the unexpected. The book reveals the deep paradox of the American dream: the belief that if you prepare enough, nothing bad will happen.

Beginnings of an empire: Stewart in her catering days, testing recipes in the kitchen that would soon become legend

And yet, there is beauty here. The photographs—shot on film, before the era of digital gloss—possess a tactile serenity that contemporary lifestyle imagery cannot replicate. The silver shines but does not gleam; the linen folds have weight. The book’s visual grammar is slow, devotional, almost painterly. In that sense, Entertaining captures something we have lost: the idea that beauty might still require patience. To host a dinner, Stewart reminds us, is to rehearse eternity in miniature.

Perhaps this is why the reissue feels oddly timely. In a culture defined by casualness and speed, Entertaining reappears as a kind of counter-revolutionary text—an artifact of discipline. Its return suggests a nostalgia for certainty, for the comfort of rules, for the illusion that grace can be manufactured. The publishers insist they have left even the dated expressions untouched. That choice feels deliberate, almost defiant. It refuses to translate the past into our idiom. Instead, it invites us to inhabit a foreign language of politeness and precision, where every verb is imperative and every gesture rehearsed.

But the reissue also exposes the hollowness of the dream it preserves. In Stewart’s world, there are no single parents, no small apartments, no late shifts or student debt. The kitchen is cathedral-sized, the pantry endless, the help invisible. What masquerades as universality is, in fact, a very specific fantasy: white, affluent, suburban, heterosexual, serene. The book’s moral force depends on exclusion. The perfect table must be protected from the mess of the real.

The prophet of presentation: Stewart in her Connecticut kitchen, ca. 1980s—the smile that turned domestic order into empire

Still, to dismiss Entertaining as relic would be too easy. Its endurance points to something deeper in the American psyche: the longing to re-enchant the everyday through ritual. Even now, amid global disorder and digital fatigue, people light candles, fold napkins, and pretend that civility can still save them. Stewart’s gospel endures because it offers transcendence without transcendence: a secular liturgy of linens and lemons. She turned domestic life into a theater of belief, and belief, in the end, is what Americans have always consumed most avidly.

What fascinates me most, reading it again, is how the photographs prefigure our era of performative living. The dinner tables look like proto-Instagram feeds—selected tableaux of aspiration, where food is less sustenance than content. But where today’s digital culture flaunts imperfection as authenticity, Stewart’s world demanded invisibility of the self. The hostess was not to emote, only to execute. The smile was part of the setting. The self disappeared into competence.

At home among copper and order: Stewart’s Connecticut kitchen staged as cathedral

Late in the book, Stewart lingers on the satisfaction of preparation—the calm that descends once everything is in place. It reads like a lesson in stoicism disguised as etiquette. The serenity she describes is not joy but dominion, the stillness of one who has conquered disorder. That calm, I suspect, is what made Entertaining a sacred text for its readers: the dream that control could feel like grace.

The reissue, however, lands in a very different situation. The table has shrunk, the attention span shortened, the idea of home fractured by mobility and crisis. The word “entertaining” itself feels antique, almost shameful, like something out of a colonial diary. We host now in fragments—brunch on the laptop, drinks on the stoop, meals delivered to couches. The labor of hospitality has been outsourced to logistics. And yet, when I turn the pages of Entertaining, I feel a strange ache: not for its perfection, but for its conviction that beauty was worth the trouble.

There is a political subtext here, too. Stewart’s aesthetic of order coincided with a national one. Reagan promised morning in America; Martha delivered the brunch. Both sold a vision of renewal through cleanliness, competence, and optimism. The spotless kitchen was the moral twin of the deregulated market: Both required invisible labor and constant maintenance. That the dream cracked by the end of the decade only adds pathos to her photographs. Behind the polished silver, one can almost hear the anxiety humming.

When Entertaining was first published, reviewers called it “aspirational,” which was code for “unattainable.” But aspiration was the point. Stewart built an empire on the gap between reality and its image. The reissue, four decades later, functions as a mirror: We no longer aspire to her world, yet we remain haunted by it. The same impulse that drove suburban women to perfect their centerpieces now drives users to perfect their grids. Order has migrated from the dining table to the digital feed, but the theology remains.

Domestic divinity: Stewart with her signature Thanksgiving tableau—abundance as moral order

If the book feels religious, it’s because it is. Stewart’s language borrows unconsciously from devotion—words like “perfect,” “graceful,” “divine.” Her insistence on ritual—polishing silver, folding napkins, arranging flowers—transforms housekeeping into sacrament. In this light, Entertaining is not about guests at all. It’s about salvation through symmetry, redemption through arrangement. It preaches that the world can be made whole if only we prepare enough hors d’oeuvres.

There is tenderness in these pages. One can imagine Stewart in her Connecticut kitchen, arranging plates in silence, believing—genuinely—that beauty matters, that it can hold loneliness at bay. To entertain, in her sense, meant to care, to pay attention, to make the ephemeral briefly eternal. It meant believing that the table, properly set, could summon grace.

Yet of course we now perceive a melancholy beneath the perfection. The more immaculate the image, the more fragile it feels. In her later years, Stewart herself would become the embodiment of that tension—the woman who taught America to roast chicken later went to prison for insider trading, but emerged unbroken, even rebranded. The empire she built began here, in these pages, with their white candles and seamless seams. Entertaining is both origin myth and cautionary tale: a nation’s dream of control meeting its appetite for collapse.

The fall and its performance: leaving federal court in 2004. The empire briefly cracked, but the brand endured.

To look at the book now is to see America’s twin obsessions—purity and performance—fused into one glossy object. It is a handbook for an empire of manners, confident that civilization begins with centerpieces. The reissue feels less like nostalgia than diagnosis: We are still living in the house Martha built, though the windows are cracked and the guests have stopped coming.

I close the book and think about the American dream—not the frontier one of expansion, but the interior one of order. The dream that the domestic can redeem the political, that surfaces can save souls. In 1982, this faith looked triumphant; in 2025, it looks tragic and oddly moving. We no longer believe that perfection is possible, but we still photograph our breakfasts as if it were.

Perhaps that is why Entertaining feels newly relevant. It shows us what belief looked like before irony. Its perfection is out of fashion, but its yearning endures. Beneath the recipes and the rose petals lies a message that remains unmistakably American: If we cannot change the world, we can at least arrange it beautifully.

Grace after scandal: Martha Stewart with Snoop Dogg, reimagining domesticity as pop-cultural communion

I put the book down and notice my own kitchen—the crumbs, the chipped cup, the unwashed glass. It feels honest, lived in, and also a little sad. I think of Martha’s world, its relentless composure, its denial of mess. Then I think of how much mess we’ve learned to live with. Somewhere between those two extremes—the immaculate and the undone—lies a lost art: to host not as a performance, but as a gesture of faith.

That, finally, is the gospel according to Martha: not that perfection saves, but that striving for it once felt like a form of love.

Marjorie Ames (b. 1978 in Atlanta) studied the semiotics of domestic labor at the Culinary Institute of Charleston. She hosts “The Minor Plate,” a YouTube series about cooking for one and the philosophy of second helpings. Her motto: no garnish, no guests.

Cover image: The empire endures: Martha Stewart outside her Skylands estate in Maine—perfection parked in the driveway

Comments