- Elias Marin

- Aug 6, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 7, 2025

COVER TO COVER

THE LAST CENTURY OF HANDWRITING*

ELIAS MARIN

August 6, 2025

It begins with a hand—hovering above the page, hesitating, then striking—a pen nib etching its dark incision, or a pencil deepening the grain of the paper with the first tentative words. The twentieth century, despite the clatter of typewriters and the promise of mechanical speed, remained a century of handwriting. Ink was still the medium of invention, the space where literature first drew breath. Yet, even as it persisted, handwriting had already entered its twilight.

The twentieth century was the last time a writer’s handwriting mattered. Not in the austere sense it once did for a medieval scribe—when the page’s worth lay in its clarity and permanence—but in an intimate, unrepeatable way. By 1900, the printing press had long displaced the scribe, and the typewriter had begun its quiet conquest of writers’ desks. Still, the century’s defining works were born on paper, in the deliberate speed or hesitation of a line written by hand. Handwriting no longer guaranteed the survival of a book, but it remained the crucible where the work was formed, where thought met the friction of the page.

Every handwritten page is an X-ray of thought, showing the fractures and improvisations beneath the polished surface.

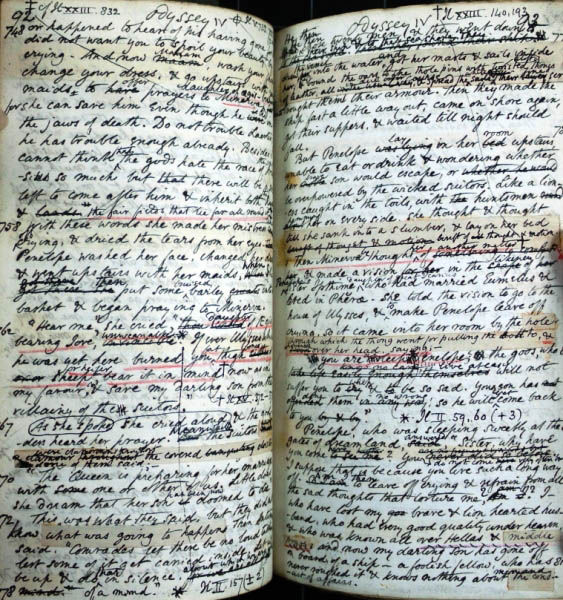

To look at the manuscript of James Joyce’s (1882–1941) Ulysses (1920) is to witness combat. The drafts are dense, unruly, crowded with marginal insertions and cramped annotations—entire paragraphs forced into the white space. Each page resembles a living organism, words curling outward, mutating with each stroke. Joyce did not merely write; he engineered, layering language as if constructing a cathedral one stone at a time.

James Joyce, manuscript page from Ulysses

Marcel Proust’s (1871–1922) ordered, fluid, almost ceremonial manuscripts display the opposite temperament. He wrote In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu, 1913–27) in bed, propped against pillows, a wooden board balanced across his knees. The pages, now preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, show his sloping, near-calligraphic hand—yet even these reveal a restlessness. Long passages appear on separate slips of paper, pinned or glued into the body of the text, like small architectural additions to the edifice of memory. His sentences are corridors of recollection. Meandering for pages, they follow the deliberate drift of his pen, as if thought itself required the material of ink to come fully into being.

Marcel Proust, manuscript pages from In Search of Lost Time

Even in the age of mechanical reproduction, handwriting retained authority. It was private, idiosyncratic, unfiltered. The printed book reached the reader, but the handwritten page was where the struggle—the thinking—occurred.

The manuscript is the most intimate portrait of the writer—messier, truer, more revealing than any photograph.

Though belonging to the previous century, Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) foreshadowed this obsession with the handwritten draft. His pages are frenetic, cramped, riddled with interlinear corrections. Writing under financial duress, in bursts of psychological tension, the manuscripts feel almost overheated. Dostoevsky wrote much of The Brothers Karamazov (1880) at breakneck speed, his quill scraping the paper as though he was trying to outrun his own thoughts. Even when he dictated, he revised by hand, layering corrections until the page itself seemed to breathe with urgency. His influence on modernist writers—Kafka, Joyce, Musil—was as much about the page’s physical energy as about theme or structure.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, manuscript page from The Brothers Karamazov

Franz Kafka (1883–1924) left manuscripts that feel uncomfortably alive. His tight, slanted script, often veering toward illegibility, suggests letters trying to escape their own formation. Drafts of The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926) are punctuated by crossings-out and hesitant marginalia, as if the author were negotiating, moment by moment, with language itself. Even his private letters to Felice Bauer and Milena Jesenská have the intensity of literary drafts, trembling with intimacy and doubt.

Franz Kafka, manuscript page from The Castle

Thomas Mann (1875–1955), by contrast, wrote with the composed authority of someone who viewed literature as a civic duty. His manuscripts for The Magic Mountain (1924) reveal a steady, confident hand, architectural in its precision. Mann’s handwriting—like his prose—seems less about personal urgency than about crafting permanence.

Robert Musil (1880–1942), author of The Man Without Qualities (1930–43, unfinished), approached his notebooks like a scientist’s laboratory. His handwriting is sharp, controlled, and deliberate, filled with diagrams, sketches, and marginalia. Each page captures a collision between fiction and philosophy, as if the act of writing were also an act of dissection.

Robert Musil, manuscript page from The Man Without Qualities

For these writers, handwriting was not nostalgic, but essential. The typewriter was a tool for producing a clean copy, but the thinking remained with pen and paper, where words and ideas could be wrestled into shape.

Handwriting is memory made visible. It records not just what was written, but how it was written—the hesitation before a word, the quick flourish of a sudden idea. A typewritten page is neutral, efficient; it reveals nothing of its own making. A handwritten page, by contrast, is all process, all story.

Cognitive science now affirms what writers have always known: Writing by hand slows the mind to the speed of its own thoughts. The act is not merely mechanical; it engages motor memory, vision, and cognition in concert. Neuroscientists have shown that forming letters on paper activates the brain’s learning centers more deeply than typing does. Each stroke imposes a rhythm, a deliberateness, as though the body itself were thinking alongside the mind. The drag of the pen, the resistance of paper, the pause before a word—these are sensory imprints, woven into the architecture of thought. Handwriting is not only expression, but a form of embodied thinking, a choreography of language and gesture that leaves traces in the flesh as much as on the page.

To write by hand is to resist speed, and in resisting speed, to find thought again.

Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) understood this intuitively. He composed novels on index cards, each card containing a scene or fragment, which he would then shuffle like a deck of possibilities. His handwriting, precise and elegant, is inseparable from the crystalline clarity of his prose. Look at the drafts of Lolita (1955), and the script seems part of the narrative’s perfection.

Vladimir Nabokov, manuscript card from Lolita

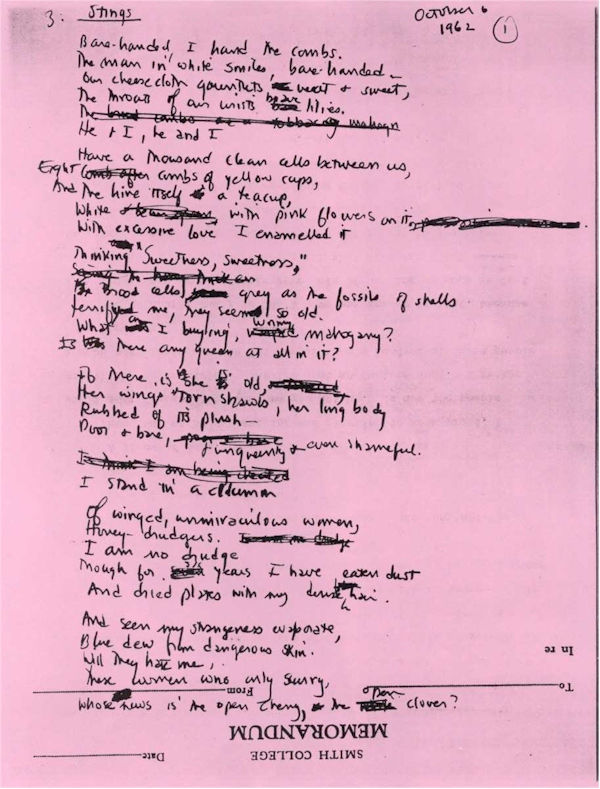

No handwriting feels as charged as that of Sylvia Plath (1932–1963). Her notebooks—part journal, part crucible—are forcefully alive. She wrote as though every word required a physical struggle. Drafts of the Ariel poems (1962, published posthumously in 1965) are streaked with crossings-out and jagged arrows, and the urgency of the language, the life behind it, is unmistakable. Her handwriting is the pulse of the work itself, vibrating with the knowledge that time was running out.

Sylvia Plath, manuscript pages from Ariel

The line of ink is never neutral; it carries the pressure of the hand, the tremor of the mind.

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) left drafts that are almost blunt in their clarity—bold, minimal, rarely tentative. Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), in contrast, wrote with a spare, almost ascetic hand, each letter a deliberate, unadorned block, mirroring the austerity of his prose and plays. John Steinbeck (1902–1968), scribbling on yellow legal pads, left pages where the pencil darkens as fatigue or frustration builds—visible evidence of the battle between story and mind.

Samuel Beckett, manuscript page from Endgame

Today, a single page of a twentieth-century manuscript can fetch more than a first edition. It is not simply the words but the artifact of creation that fascinates: a map of thought in its raw, tactile form. When Faber & Faber published facsimiles of Plath’s Ariel drafts, readers were startled by their intensity—the cuts, the ink stains, the breathless urgency. William Faulkner’s (1897–1962) manuscripts are equally physical, patched together with taped insertions that reflect the fractured loops of his narratives.

The keyboard encourages speed, but speed rarely allows for depth. In an era of cloud storage and invisible revisions, manuscripts from the last century feel like secret archives of creativity—documents of a time when a writer’s hand, with all its hesitations and errant lines, was the true instrument of thought.

The twentieth century began with fountain pens and ended with keyboards. Typewriters and computers promised efficiency, revision without mess, the luxury of deletion. But something was lost—the sense that writing is not merely the manipulation of language but a bodily act, bound to gesture, pressure, and time. To see a manuscript by Nabokov or Kafka is to be brought closer to the moment of creation, to a line of ink still warm with the trace of its author’s pulse.

What is vanishing is not handwriting, but a form of intimacy between thought and its trace.

In the end, it always returns to a hand. The hand that sharpened Steinbeck’s pencils, scattered Kafka’s drafts across a Prague desk, or pressed Plath’s words into paper with urgent finality. The twentieth century may have been the last era to honor the private choreography of ink and mind, but the pages that have come down to us—often creased, smudged, or luminous with revision—remind us that literature is, for all its abstraction, a physical act. A sentence is not just written; it is made.

*Note from the editors: The present essay was submitted entirely in handwritten form—an admirable gesture, though one that defied legibility. After several failed attempts at decipherment (including a brief consultation with a graphologist), we opted to retype the text. For purists and the handwriting-curious, a PDF of the original manuscript is available upon request.

Elias Marin (b. 1969 in Porto, Portugal) is a critic and literary scholar based in Helsinki. His essays often explore the tension between technology and memory, from the fading craft of handwriting to the digital eclipse of narrative form. He is the author of “The Invisible Page: On Literature Before the Screen” (2021), a study of twentieth-century manuscripts and the decline of the writing hand.

Cover image: Who can measure the heat and passion of a poet’s heart when it is caught and tangled in a woman’s body? Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own (1929)

Comments